This article below was written by the previous owner of bondreview in May 2021. It is being published because now that High Street GRP Ltd is in administration it will be interesting to see whether or not the prophecies came true. This article is 11 months old so it will obviously have been overtaken by events later in 2021.

Safe Or Scam has written two articles on the High Street GRP Ltd administration on its blog page.

May 2021 Article

An article from Business Live reveals that High Street Group has called a meeting with creditors in an attempt to delay repayment of its bonds.

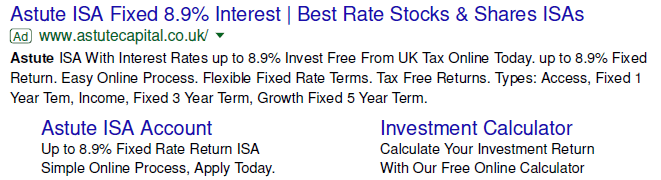

The meetings relate to 7 year bonds issued by High Street Group, which I believe are the ones issued with an interest rate that started at 12% per year and escalated to 22% in the 7th year. Bondholders had the option to redeem their bond at each anniversary.

12% fixed annual return (bonuses available from the 2nd year).

Flexible 1 – 7 year investment period.

All funds secured against significant unencumbered assets.

Debenture and Corporate Guarantee held by an FCA regulated Security Trustee.

No exit fees or hidden costs such as stamp duty, legal fees, service charge, ground rent and general maintenance.

Exit option every 12 months.

The money will be provided for acquisitions for the High Street Group – thehighstreetgroup.com/ – funds are used for multiple projects, this is yet another security in place as you are backed by all the assets values, not just one.

2019 third party introducer promotion for High Street Group’s unregulated 7 year bonds. Typos as per the original.

According to Business Live, High Street Group is seeking to renege on that “exit option” to redeem the bond at each anniversary. It warns that if investors do not agree, the company could collapse.

It is asking investors to scrap a condition that allows them to redeem investment before the end of a seven-year bond, and warns that if it fails to get approval, it could have to review the company’s ability to continue as a ‘going concern’.

I believe these particular 12%-22%pa terms were first offered by HSG in 2019. That would mean investors are effectively being asked to defer the right to repayment from 2020 to 2026 – a dramatic change to what investors signed up for. We can call the right to redeem in 2020 “early” redemption, despite its introducers using the word “flexible”, but in the end investors either have the right to demand their money back or they don’t.

Naturally, even if HSG’s creditors do all defer their right to 2026, there remains the same inherent risk of up to 100% loss that exists with any loan to an unregulated, unlisted company, only with five extra years of waiting.

The Business Live article refers to investors as “shareholders” – but as far as I’m aware the investments in question were structured as loans, not shares. Indeed, the promotion above specifically referred to “loan notes” and to a “debenture [another name for a loan] and corporate guarantee”.

According to High Street Group, 50% of investors have already agreed to the new terms.

It is however important to note that a majority of High Street Group’s creditors agreeing to defer payment has, in itself, no effect on the right of other creditors to enforce their debt.

For creditors to be able to vote on a renegotiation which affects all creditors generally requires a formal insolvency procedure, such as a Company Voluntary Arrangement or administration. All such options involve the apppointment of insolvency practitioners. High Street Group as a whole continues to trade and is not in administration (though a subsidiary, High Street Rooftop, is).

So High Street Group can call as many meetings with its creditors as it likes, but any of its creditors whose loans have fallen due will retain that right, unless a) they individually give it up or b) the company enters a formal insolvency proceeding. Unless there’s something very specific in the terms of the loans giving the company the right to change them.

In attempting to persuade investors to give up their right to flexible redemption on the bond anniversary, High Street Group attempts to compare itself with mainstream regulated commercial property funds.

This measure is not unusual, in fact during the pandemic the FCA gave permission for investment firms to pause redemptions in order to maintain the viability of the sector.

What HSG are referring to here are open-ended commercial property funds which, in benign circumstances, allow investors to redeem their investment on a daily basis (as it stands; the FCA is running a consultation into whether they should have a notice period). This is a far cry from HSG’s unregulated bonds which would only be redeemable annually even in the best of times.

Clearly, a fund holding illiquid commercial properties cannot meet sale requests within 24 hours if more investors want to get their money out than the fund has in cash in the bank. When this happens, open-ended commercial property funds suspend withdrawals, typically for months to give themselves time to sell properties without a fire sale.

They did not, as HSG claim, require FCA permission to do so. In reality, it is mandatory for an open-ended commercial property to fund when it has more withdrawal requests than cash on hand. This not only happened during the 2020 coronavirus crash, but in the 2016 Brexit crash and the 2007 commercial property crash before that. It is an inherent and normal feature of investing in an illiquid asset via a fund that commits to allowing you to cash out at the Net Asset Value of the properties. (In contrast to “closed-ended” funds, such as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), where you can usually cash out via the stock exchange even in times of crisis, but only if you accept a substantial discount to the Net Asset Value.)

HSG’s attempt to compare itself with mainstream commercial property funds is not flattering to HSG. Most open-ended commercial property funds, having universally closed en masse during lockdown, have since re-opened. Some have already recovered the falls in value during the pandemic. Of the two I can name that remain closed, one plans to open by the end of June (Aegon) and another has announced that it will be wound up (Aviva) – but has said it intends to return 40% of the fund to investors by July, with the rest to follow within a couple of years as it sells properties.

Which, while highly disappointing to Aviva investors, is more transparent than the 5-year timeframe for any returns that HSG investors are looking at, with the inherent risk of 100% loss remaining that comes with any loan to an unregulated company.

But mainstream regulated funds don’t promise returns of 22% per year if you stick with them for 7 years (with an average return of c. 17%pa over the 7 years), so here we are.

“Accounts due soon”

The Business Live article understates High Street Group’s difficulties in complying with the law when it refers to “a number of accounts being filed late”. It later states inaccurately “High Street Group’s 2019 accounts are five months overdue”. The December 2018 and December 2019 accounts for High Street Commercial Finance, one of the companies that has raised money from bondholders, have never been filed at time of writing (not filed is different from filed late). The December 2018 accounts are a year and a half overdue. The holding company, High Street Grp, is five months overdue with its December 2019 accounts (having finally filed the December 2018 accounts, which received an adverse opinion from its auditors). From the perspective of investors who loaned it their money, High Street Commercial Finance Ltd = High Street Group. HSCF is also five months overdue with its latest confirmation statement (details of who owns the company).

According to Business Live “it is believed publication [of the accounts] is due soon”. How soon and who believes this is not specified.

High Street Group continues to blame the Covid pandemic for its issues.

The company said in February that it had suffered difficulties after the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) allowed investment groups to suspend lending during the coronavirus pandemic.

This overlooks the fact that High Street Group’s issues with filing accounts started in September 2019, when it fell overdue with the 2018 accounts for High Street Commercial Finance, when Covid was just a twinkle in a pangolin’s eye.

There are a number of comments under my original review referring to problems obtaining repayment from HSG. The first of those explicitly referring to HSG delaying repayment was in November 2019.

Some months before that, investors had referred to being offered repayment in shares rather than cash. A company confident in its growth prospects (which is certainly the case for HSG based on its investment literature) only offers to repay investors in shares if it is short of cash. Otherwise the shareholders would keep their shares and the rising value of them for themselves. Again, all this was months before Covid hit the UK in earnest.

According to the Business Live article, High Street Group has announced a £172 million deal with the Edmond de Rothschild Real Estate Investment Management group.

No details are provided in the article as to how much of these funds will be available to repay HSG bondholders.