Roger Allanson, owner of the eponymous Allansons LLP unregulated litigation funding investment scheme, has been struck off as a solicitor and ordered to pay the Tribunal’s costs of £103,868.

The scheme claimed to deliver a potential return of 50% in a timeframe of 6-18 months.

Third-party unregulated introducers soliciting investment into the scheme claimed that the investment was covered by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, thanks to a complex structure involving an insurance broker offering an unauthorised credit default swap and an “After The Event” insurer in Bermuda. Exactly who dreamt up this claim is unclear as it never formed part of Allansons’ own marketing (only their introducers’); while the Tribunal case does centre on misleading claims of “no risk” made in Allansons’ marketing, the FSCS coverage claim is not one of them.

The allegations against Allanson were:

- That the marketing material used to solicit investment into the scheme was misleading.

- That the monies invested were “misused”, with either 24% or 4% of each investment retained by Allansons, and a total of £347,000 of payments made either to introducers or Allanson himself that breached the solicitors’ Code of Conduct.

- That Allanson failed to monitor the mortgage overpayment claims that underpinned the investment scheme.

- That Allanson sent “inappropriate” emails to an investor who was querying the status of his investment.

- That Allanson failed to maintain adequate accounting records and client account reconciliations.

- That Allanson failed to maintain client ledgers for the over 4,000 clients whose cases against their mortgage lenders underpinned the investment scheme.

Checkered history

The investment scheme centred around mortgage borrowers who had supposedly paid too much in interest to their lenders.

Allansons began taking on a handful of claims in December 2016, but the vast majority of cases were taken on in 2018 after the litigation funding scheme ramped up. Of 7,773 cases taken on by Allansons at 31 January 2019, 99.7% were taken on in the preceding 12 months. (The Allansons scheme was reviewed here in January 2018.)

The cases were heavily reliant on a piece of software called “Checker Reports” developed by a man the Solicitors Tribunal refers to politely as “Mr BT”, director of “MAS Limited”. This would almost certainly be Bryan Turner of Mortgage Audit Services Limited, who featured in Allansons investment literature.

“Checker Reports” was put into action in relation to the “Brothers H” (apparently someone at the Tribunal is a Dostoevsky fan), who had defaulted on a number of commercial mortgages with Santander. Before Checker Reports entered the scene, Santander had already conceded an overpayment of c. £29,000 to the Brothers H as a result of a Financial Ombudsman case.

In late 2012, armed with a printout from “Checker Reports”, Roger Allanson demanded Santander refund a further £114,000. Santander refused, stating “the recalculation method to reach this figure is incorrect”. Nonetheless Santander did reduce its claim “a bit further”, settling for the proceeds of the sale of the Brothers H’s property – but clearly not for a £114,000 repayment.

This single case was trumpeted as a “proven track record” in Allansons’ literature. In the Tribunal’s words, the investment literature claimed that the Checker report had been a “silver bullet which had solved Brothers H’s problems”. In reality, the return of £29,000 by Santander was the work of the Financial Ombudsman, not the Checker report, and the claim for a further £114,000 on the basis of the Checker report had been mostly tossed out by Santander. Plus a negotiated agreement not to pursue the Brothers H for money in excess of the property sale proceeds (i.e. money they probably didn’t have).

The Tribunal rejected a submission by Allanson that a single (shaky) case could constitute a “proven track record”.

This was one of a number of points found to be misleading by the Tribunal. Other points found to be misleading in the investment literature included

- The impression that the investment carried no risk of loss. A FAQ claimed that the only “risks of investing” were “you might not receive a return on your investment… there is ATE insurance in place in the event a case fails.”

- The impression that investors’ money would be spent only on an expert audit report, with other costs covered by Allansons, whereas in reality investors’ money was funneled to introducers and Allansons itself.

- A claim that the chances of success had been reckoned at 75%, without mentioning that this was based on legal advice that had been heavily circumscribed and caveated. One of the lawyers who had been used to back the “75%” claim told Allanson that her advice had been mischaracterised and demanded that he remove reference to her practice from the literature.

Misuse of money and 20% commissions

In an email to a much-abused (in every sense) investor called “Mr AL”, Allanson claimed

No commissions, excessive or otherwise have been paid to agents. I do not have any agents.

In reality Allansons was paying commission to a number of introducers, identified only by initials in the Tribunal report.

The Litigation Funding Agreement signed by investors stipulated that funds would be used “specifically to pay for the Checker expert reports and necessary case costs only”. In reality they were used to prop up the law practice (including to pay off the company credit card) and to pay a number of introducers. The Tribunal found that this was a misuse of investor money and contrary to the investor agreement.

Allanson claimed that introducers were due 20% of investor money “payable at case close”. The SRA’s solicitor pointed out that introducers were unlikely to wait until the closure of the legal cases for their money, given they had no oversight or control over those cases. She also pointed out a number of transfers out of the scheme’s bank account to introducers.

£19m invested, not a penny recovered

A total of £19 million was raised from investors in the Allansons’ scheme, and paid out.

Not a penny was recovered from any mortgage lender as a result.

The case against Allansons details a “litany” of failures in progressing the cases, and delays of up to nine months after a potential client had signed an authority before a “letter before action” was sent to the lender.

None of the case files had an individual Counsel’s opinion assessing its merits.

Mortgage lenders who received claims in respect of Allansons clients were left scratching their heads over what the claim was supposed to be about.

The most common cause of delay was that the letter of claim was insufficiently detailed and the lenders were unable to understand what claims were being made, and how those were supported by any calculations.

The Tribunal noted that in the 18 months that the scheme was running, the Respondent did not recover a penny from any lender. He had not issued any claims, nor had he sent any Part 36 offer letters. He had collected from litigation funders, and paid out, over £19m. In not one case had any lender indicated any intention to do other than reject the claims. In not one case had the Respondent provided a detailed exposition to a lender of why there was a good claim and how it was particularised.The letters before action had not been in the proper form, leading to their rejection.

The Tribunal found that up until 2018, Allanson’s strategy had been to overwhelm lenders with a large mass of claims with the threat of charging them £4,000 for a detailed report which didn’t exist. In 2019 the SRA intervened, as Allansons was preparing to change tack by issuing 20 test cases.

Allanson at this point deployed the familiar “everything would have been fine if the regulator hadn’t shut us down” cliché.

The Tribunal was satisfied that in reality, the Allansons scheme collapsed because Allanson was better at raising money from investors than actually using it to fund cases.

The Tribunal was satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the Respondent had failed to adequately manage the progression of the MMP claims and so found the factual basis of Allegation 1.3 proved.

“It’s better to keep your mouth shut and appear stupid than open it and remove all doubt”

Allanson was also sanctioned for “inappropriate” emails sent to the aforementioned Mr AL, who had become concerned about the progress of his investment and started to regularly contact Allanson. Allanson responded by questioning Mr AL’s intelligence and threatening to sue for defamation.

The fact you make wild assumptions to support your personal hostility towards me makes damages for defamation top of the agenda for the meeting yet to come. Mark Twain once said “it’s better to keep your mouth shut and appear stupid than open it and remove all doubt”. I can’t think why that sprang to mind, but curiously it did. Still want to meet?”

Email by Allanson to one of his investors

The Tribunal rejected a claim by Allanson that the email was jocular in nature and an attempt to defuse the situation. It also noted that the allegation of defamation was nonsense as Mr AL’s allegations had only been made to Allanson himself, not to a wider audience.

(Trained solicitors not understanding the basic requirements for a claim of defamation? Whatever next?)

Findings

The Tribunal found:

That Allanson’s systemic failure amounted to manifest incompetence.

The Tribunal considered whetherthe Respondent’s conduct amounted to incompetence that was so clear and obvious as to rise to the level of manifest incompetence. This was not a failure on one or two files but a systemic failure on thousands of files, funded to the tune of over £19m. The failures were basic and repeated, and the Tribunal was satisfied on the balance of probabilities that it clearly amounted to manifest incompetence.

The Tribunal also found that Allanson demonstrated dishonesty in regard to the misleading marketing material and his claims to an investor that no commission had been paid out of their investment.

The various allegations to do with failure to keep adequate accounting records were also found true.

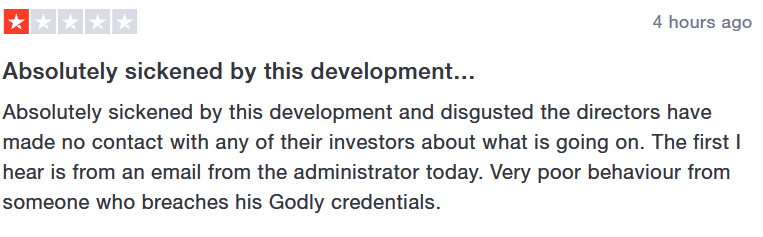

The Tribunal found that Allanson had been motivated by financial gain, contrary to his claims of “a wish to help others”. Which in the context of a £19 million investment scheme which made not a penny in returns is a bit like finding that Casanova had a tendency to think with his wedding tackle.

As a consequence of the Tribunal’s findings, Roger Allanson was struck off as a solicitor and found liable for c. £104,000 in costs.

Allanson pleaded poverty in an attempt to persuade the Tribunal not to apply costs. He claimed that as a result of the Tribunal case he is currently working for a builder at £10 per hour, dependent on his wife, and a self-described “man of straw”.

He also made “a number of personal attacks on the integrity of various individuals involved in the preparation of the case”. The Tribunal paid no attention to his conspiracy theories, dismissing them as “unsubstantiated”.

The Tribunal rejected his plea of poverty, noting that Allanson received “unexplained” funds from his investment scheme and therefore had not proved that he could not afford the costs.

the Tribunal noted that he had received money as a result of the scheme that had not been explained. In the absence of that information the Tribunal could not conclude that the Respondent was unable to pay the costs.

Allansons LLP was put into voluntary liquidation in May 2020. Investors’ money in was reported as a debt and investors’ money out reported as an asset, meaning the liquidator is responsible for recovering any investor funds that can be recovered. (If any.) Progress reports for voluntary liquidations are due annually (unlike administrations where reports are required every six months) so the first should be due soon.