The collapse of Blackmore Bonds has once again laid bare the Financial Conduct Authority’s institutional contempt for its objective of consumer protection.

Paul Carlier, an independent consultant known for blowing the whistle on dodgy FX dealings at Lloyds, contacted the FCA on March 2017 to warn them that Blackmore Bonds’ high-risk investments were being missold by an unregulated introducer named Amyma.

They occupy the office next to us and the glass partition means we hear everything they say and do.

In a nutshell Boiler Room. […] They are pushing all manner of these bonds to pensioners citing them as “guaranteed by one of the worlds biggest banks”. […] “Everything is guaranteed” “I’ll put you down as a sophisticated investor”.

[…] And their phone rarely ever rings and assume from the fact that they have to ask people’s names that cold calling in some form is involved.

Carlier received a reply from the FCA to say that his report would be passed to “the relevant areas to consider”. Carlier replied

Please stress to whomever you pass the Amyma info to that pensioners are clearly being targeted.

It’s not just a Boiler shop issue but activity related to misleading pensioners, vulnerable under the new rules.

Carlier continued to press the FCA on the subject over the following years, but the FCA refused to engage with him regarding Blackmore Bond or Amyma.

Carlier was not the only one to warn the FCA long before Blackmore’s collapse. I can reveal that I also contacted the FCA to warn them of the same thing, a year after Carlier did, in early 2018.

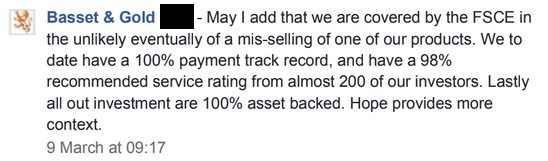

I highlighted to the FCA a) the misleading way Blackmore was advertising its bond via social media, with terms like “Income Certainty” “Knowing how to invest your savings doesn’t have to be difficult” etc. And b) how Trustpilot laid bare how many Blackmore investors clearly did not qualify as high-net-worth or sophisticated.

Like Carlier, I never heard anything back beyond a boilerplate acknowledgement.

So what did the FCA do?

Amyma has also marketed Asset Life plc (now insolvent) and Westway Holdings (trading but in default of its obligations to investors).

The only action taken by the FCA in regard to Amyma that is in the public domain was to give it FCA authorisation, via the firm Equity for Growth (Securities) Limited. Amyma Ltd was an Appointed Representative of EfGS from July 2018 to September 2019. This means that the FCA did not authorise Amyma directly; EfGS was ultimately responsible for Amyma’s contact during that period. Why Amyma lost its appointed rep status in 2019 is not publicly known.

In 2019 Blackmore rowed back on its promotional activity following the collapse of London Capital and Finance, first closing to new business and then re-opening to non-UK investment only (despite there being no legal prohibition on it accepting money from within the UK).

However, no action was actually taken by the FCA against Blackmore that is in the public domain. Which given that Blackmore’s bonds were promoted to the general public is the same thing as no action being taken.

Regardless of what happened in the year leading up to Blackmore’s collapse, Blackmore was able to continue misleadingly marketing its bonds via its own social media and via third parties for years after the FCA was made aware of it.

Institutional contempt

Former FCA head and now Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey admitted in June 2019 that the FCA was aware of the systematic misselling of LCF bonds long before it intervened in December 2018. That it did the same with Blackmore is not a surprise.

Why does the FCA focus so much of its attention on issues such as the minutiae of “worst regulation ever” Mifid II, finger-wagging over easy access interest rates, hanging out with Arnold Schwarzenegger and chin-wagging conferences about excellent sheep; while over a billion pounds is lost on the UK on systematically missold unregulated investments, with far-reaching consequences to the wider economy and society?

This is not a rhetorical question.

The tea within the financial industry is that the FCA takes the view that banks underpaying their depositors by £1 billion is more important than people losing £500 million worth of life savings in scams or unregulated investments.

This comes from second-hand reports of private conversations with FCA officials, and the FCA will never verify this in public, so readers can take it or leave it. Personally I take it, because it is a model which consistently explains the pattern of FCA behaviour over a period of many years.

This “£1 billion of uncompetitive interest rates is more important than £500m of lost life savings” credo is of course complete nonsense.

Studies have consistently shown that the stress and misery caused by losing your life savings is comparable to that of losing a limb or a loved one.

By contrast, customers being overcharged for insurance or receiving 0.5%pa less than the best-buy rate causes precisely no misery whatsoever. If it caused them misery they would switch.

If the police took this attitude to crime prevention and prosecution, shoplifting would be priortised over murder on the grounds that £100 stolen from a shop is more important than £50 worth of clothing getting covered in the victim’s blood.

The idea that some banks paying less interest than others is more important than scams because the first involves more money, is a classic example of starting from the conclusion you want and then finding a reason to justify it.

The reason the FCA pays virtually no attention to the loss of hundreds of millions worth of savings in inappriorate high risk unregulated investments is because they view it as beneath them.

The FCA would rather be a vicar than a sheriff. Regulated businesses serve the FCA tea and biscuits in nice London offices and nod attentively when it lectures them about the font they use to disclose their charges. The FCA would rather eat their biscuits than drive up to grotty offices in Bournemouth and Bolton to serve cease and desist notices. But the latter is where action is needed.

We have gone way beyond “Why doesn’t the FCA do something?” The answer to that is the same as when the frog asked the scorpion “What did you do that for?” The question is now “When will Parliament do something about the FCA?”

The FCA has now been leaderless for four months and counting.

The last time the FCA was under interim leadership, London Capital and Finance obtained FCA authorisation, allowing the marketing of its bonds to go into overdrive.

I was tempted to conclude this article “Round and round we go” and call it a morning, but the reality is that the cycle can be broken. We also know how it can be broken.All investment security offerings registered with the FCA, as has been the case in the USA for almost a century, and a top-down reform of the FCA to bring about real and urgently needed cultural change.

It is now up to the Government to choose whether to break the cycle or throw future pensioners and other vulnerable consumers on the bonfire.

Footnote – Philip Nunn speaks – or doesn’t

Blackmore director and co-owner Philip Nunn remains active on Twitter, but appears to be pretending his most famous company doesn’t exist.

Since Blackmore collapsed into administration, Nunn has not had a word to say to his stricken investors, instead restricting himself to offering his services for raising investment in the cryptocurrency industry, and banal nonsense along the lines of “2018 – Everyone is a Bitcoin seller. 2020 – Everyone is a PPE seller.”

Since October 2018 (as far back as I could go), Nunn’s Twitter feed barely mentions Blackmore at all.

Also notable is that in a puff piece in 2018, Philip Nunn was still being introduced as “CEO of Wealth Chain Group and The Blackmore Group”. However, by 2019 Nunn was being mentioned in puff pieces only as CEO of Wealth Chain Group, with no mention of Blackmore.

This is odd because Wealth Chain Group is an obscure one-man band. (A one-man band that owes money to Blackmore companies, according to its 2018 accounts; its 2019 accounts are overdue.)

If you were the owner of two businesses, one a £45 million property firm, and the other an obscure one-man band, why wouldn’t you identify yourself first and foremost as head honcho of the property firm? Especially in 2019, long before the property firm collapsed, when it was still telling everyone that it was on doing great and on course to meet all payments to investors?

Patrick McCreesh by contrast has not updated his Twitter feed since May 2018. Until that point his Twitter activity mostly consisted of retweeted and self-penned Blackmore PR announcements.

The FCA is probably hoping that everyone forgets Blackmore existed as well.