[An expanded version of a Twitter rant posted last Monday ago.]

According to IFA trade rag Money Marketing, investors in London Capital and Finance are very angry that the Financial Conduct Authority has repeatedly referred to the loan notes in which they invested, marketed by LCF as “secured bonds”, as mini-bonds.

So what is a mini-bond and why are LCF investors annoyed about the label? The FCA says (in an article belatedly posted last month) “There is no legal definition of a ‘mini-bond’, but the term usually refers to illiquid debt securities marketed to retail investors.”

The crucial characteristics of a mini-bond are:

- It is unlisted. If it is listed on a major stockmarket, like bonds in BT or major banks or investment trusts, it is a listed security. Debt issues listed on major stock exchanges are often worth hundreds of millions or billions and therefore too big to be a “mini-bond”.

- It is issued directly to the public (aka retail investors). If it is issued to institutions it is a business loan. “Mini-bond” is a marketing label and business loans aren’t marketed, therefore to be a mini-bond it has to be marketed to the public.

The market for “mini-bonds” took off in 2010. The economy was recovering and people had money burning a hole in their pocket. But the banks, chastened by the credit crunch and recently tightened capital adequacy rules, were hanging on to theirs. So a few companies had the bright idea of borrowing money directly from their customers.

Among the most famous examples were Hotel Chocolat (whose bonds gave you the option of being paid in chocolate), the Jockey Club (whose bonds could pay you in racecourse tickets), and John Lewis.

Although this kind of investment took off in 2010, the “mini-bond” label seems to have gained currency around 2013. A 2013 Guardian article uses the term alongside “passion bond”.

This reflects that the target market for mini-bonds was not people trying to grow their money (like LCF investors), but people who were already fans of the company issuing the bond.

Why “mini-bonds”? Partly because of the small size of the amounts raised: typically 6 or at most 7 figures rather than the hundreds of millions or billions raised in listed securities by FTSE 100 firms.

But mostly because the term “mini” cosily implies that the bond issue poses no danger, despite the inherent risk of 100% loss. The complacent regulatory consensus was that no-one in their right mind would invest all their money in a bond paying interest in chocolate or racecourse tickets or burritos (seriously). The target market was not people trying to secure their financial future, but well-off fans of a company who could afford to invest a few thousand and wouldn’t mind even if they lost all of it.

The “mini-bond” label gained currency so quickly (leaving alternatives such as “passion bonds” to be forgotten) because of its cosy connotations of harmlessness. It was a tacit linguistic accommodation between the regulator and the promoters of the investments.

Who cares if an unlisted investment in a small company is inherently high risk? Does it really matter if all the investors have filed documentation with the company proving that they are high-net-worth or sophisticated? Nobody’s going to lose their life-savings investing in bonds paying interest in chocolate.

The “mini-bond” label allowed the FCA to indulge in its favourite kind of regulation, i.e. “masterly inactivity”, or classifying things as insigificant and not its problem, regardless of how many FSMA offences are being committed and how many people are being harmed.

But it is a truth universally acknowledged that investors throwing money at unregulated investments without meaningful due diligence are in want of being scammed.

Soon the first wave of companies were springing up out of nowhere offering minibonds offering attractive-sounding rates and some kind of spiel suggesting it was as safe as houses (secured loans, subsidised renewable energy, sheltered housing, blah blah). They were not targeting investors willing to lend a few thousand in return for “our favourite customer” status, but the mass of people fed up with losing money to inflation, but inexperienced and unaware of how to get a higher return without risking permanent loss.

By 2013, alarm bells were being sounded. Purple prose about “innovative” and “ethical” investments was out and risk warnings were in. No article about the amounts raised by minibonds was complete without a warning about the inherent risks. The aforementioned 2013 Guardian article’s subheading ended “…names such as John Lewis are issuing their own retail bonds, but analysts advise caution”.

By 2015 the mini-bond label had gone sour. In September 2015, the Guardian ran an article entitled “If you see something promoted as a ‘mini-bond’, bin it!” after the £7m collapse of Secured Energy Bonds. At the time, SEB’s FCA-regulated agent, Independent Portfolio Managers, had just completed raising another £7m for Providence Bonds. Providence Bonds also later collapsed with total losses.

A year later London Capital & Finance secured authorisation from the FCA, allowing it to turn its promotional activity up to 11 and use the FCA-authorised label to raise £230 million while reassuring investors that it was “safe as houses”. But it was in mini-bonds, so the FCA ignored it. Three years later, after the FCA could no longer ignore LCF’s misleading advertising, LCF duly collapsed as well.

It is no surprise that LCF investors are bemused and angered by the “mini-bond” label. The LCF bonds were not sold as “mini-bonds” but “secured bonds”, referring to investors’ “secured creditor” status. This is not surprising, given that by 2015 the “mini-bond” label was already toxic.

“Secured bonds” was in reality just another marketing label. The “secured creditor” status in reality gave virtually no meaningful security, as a) it is clear from the administration that there are in reality very few assets of value in LCF, and b) secured investors made up by far the largest category of creditors, so it would barely have made much difference if investors had been unsecured creditors instead.

This, perhaps, explains LCF investors’ anger. As I have said before, they are the last person to find out that their spouse is the village bicycle and all their friends and acquaintances have been laughing at them.

It is not just that they have been duped, but the feeling of betrayal that comes from knowing that other people knew and didn’t tell them.

The fact that alarm bells were being rung in 2013 and 2015 and onwards shows that this is not about hindsight. We are talking about a consistent regulatory policy which has had predictable and consistent results.

Everyone who was aware of what LCF was and had a basic level of financial understanding knew that LCF investors had been duped about the risks of LCF and were highly likely to lose their money. But nobody told the investors because either

- they couldn’t get the word out (most of the general public)

- or they were afraid of being sued (the media)

- or they had both a public voice and immunity from being sued, but they didn’t give a shit. (The FCA.)

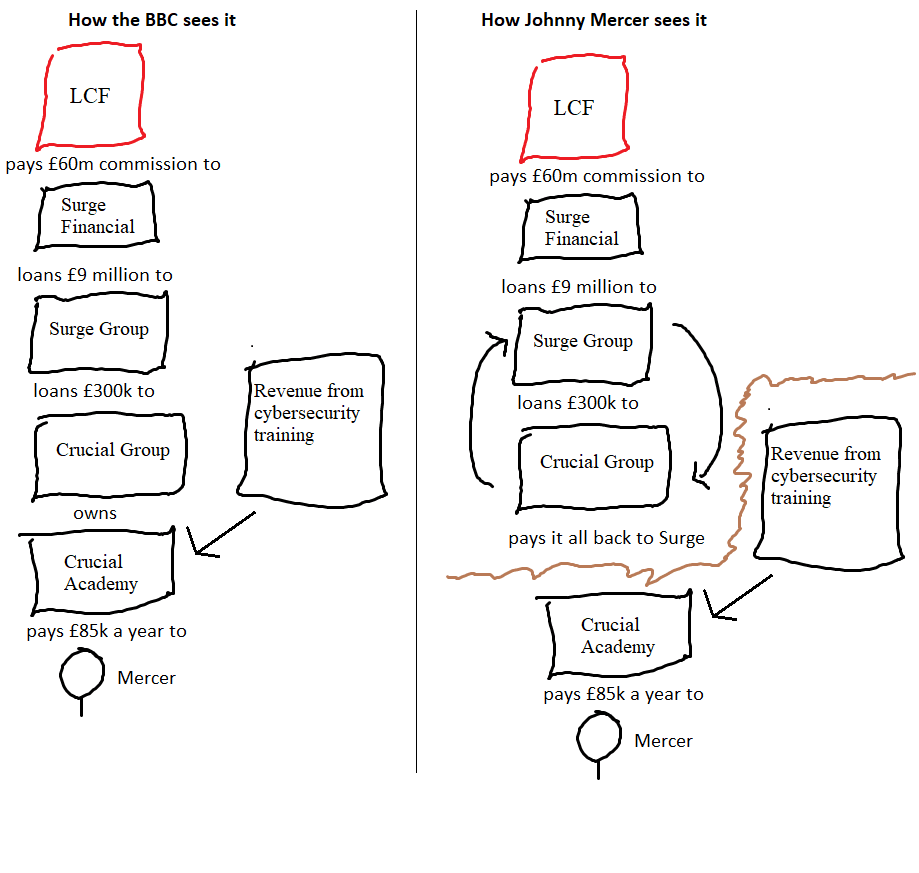

Johnny Mercer MP’s appearance on Have I Got News For You didn’t reach the heights of car-crash TV and may not even make the end-of-season highlights episode. It may however make it into the textbooks of law students – to my knowledge, no-one has ever sued a corporation for libel and then immediately appeared on a comedy panel show hosted by that corporation to state their position.

Johnny Mercer MP’s appearance on Have I Got News For You didn’t reach the heights of car-crash TV and may not even make the end-of-season highlights episode. It may however make it into the textbooks of law students – to my knowledge, no-one has ever sued a corporation for libel and then immediately appeared on a comedy panel show hosted by that corporation to state their position.