Betteridge’s Law of Headlines: Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered with the word “No”.

As I noted earlier this week, in July and August Independent Portfolio Managers had what is bound to be the first of many Financial Ombudsman complaints awarded against it, for its role in approving the literature for the collapsed Secured Energy Bond investment.

It looks highly likely that similar awards against it will follow for its role in Providence Bonds.

In June 2018, the Financial Conduct Authority cancelled IPM’s permissions over an unpaid regulatory fee of £1,660 and 23 pence. The chance of IPM being able to meet the slew of claims against it, which could run into the millions, appears minimal.

Secured Energy investors still however appear confident that they’ll get their money back – on the basis that the Financial Services Compensation Scheme will pay up when/if IPM goes bankrupt.

At time of writing, the two test case investors have accepted the ruling, so IPM has now been ordered to pay. IPM is no longer an FCA-regulated company. If it fails to pay, investors have to go to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme. More delays, but eventually I should see my money back.

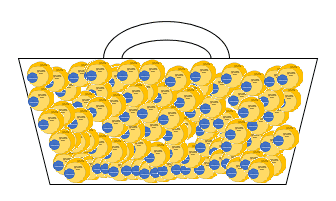

I hate to be ‘that guy’ towards investors who have suffered enough already, but if the FSCS compensates Secured Energy investors for their unregulated, ultra high risk investment, it will effectively turn the entire UK financial system on its head and mean that any unregulated capital-at-risk investment can be rendered risk-free for any investment below £50,000 (£100,000 for couples).

(This point appears to have been missed by the Guardian and other outlets which have covered this story; understandably, they have focused on the long emotional struggle of investors and not the detail of financial services regulation.)

How to make an unregulated investment risk-free (if the FSCS pays out over IPM)

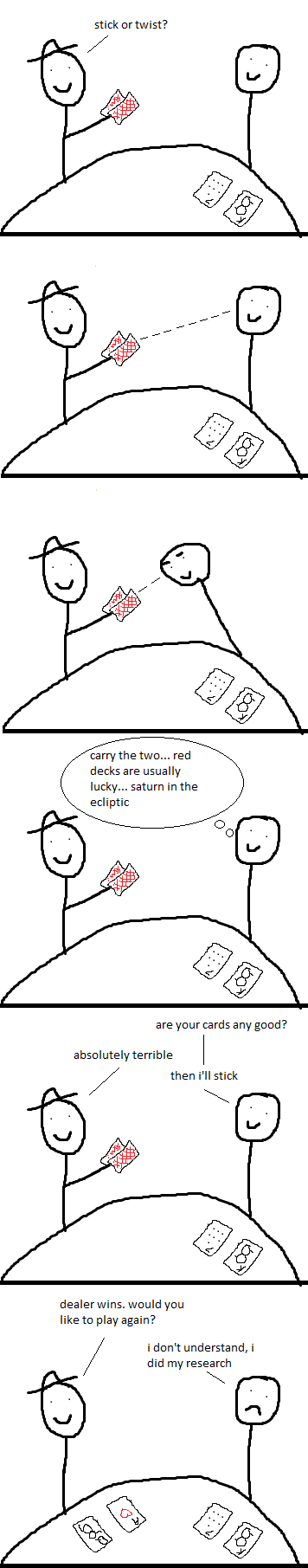

- I launch Company X offering unregulated bonds offering returns of 8% per year for investing in whatever (let’s say crypto mining).

- Simultaneously my friend sets up Company Y and applies for FCA authorisation to conduct whatever regulated activity is the easiest to get FCA authorisation for.

- Once FCA registration is secured, my friend rubber-stamps my investment literature with the words “approved for the purposes of Section 21 of the FSMA by Company Y, which is authorised and regulated by etc etc”.

- Both of us ensure we are careless enough that there is a clear error in the investment literature – such as overegging “security features” to make the bonds appear less risky than they are (as with IPM).

- A few years later Company X goes bust. Investors complain to the Financial Ombudsman that the literature was misleading and Company Y should have spotted it.

- The Ombudsman upholds the complaints and awards redress against Company Y. Company Y goes bust.

- Investors claim to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme and get their money back (up to £50,000 per person).

There are, of course, already a total of three ways in which you can transfer liability for an investment scheme to the FSCS.

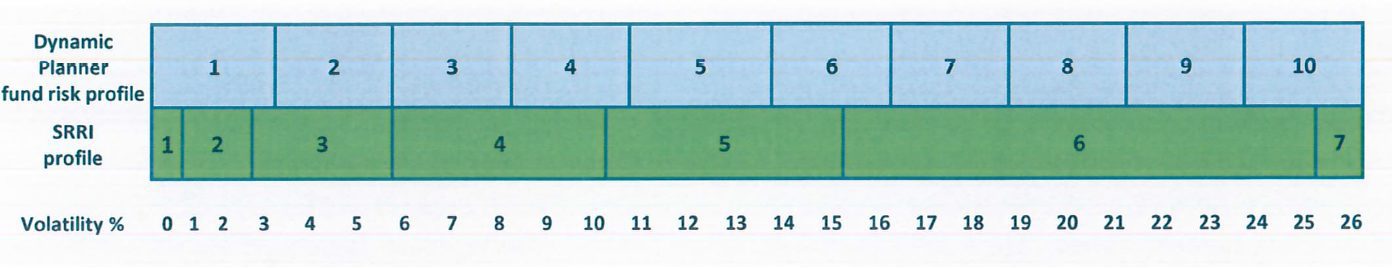

- Set up an authorised deposit-taker and issue retail deposits or cash ISAs (which are FSCS-protected). Problem: getting authorised as a deposit-taker involves extremely stringent regulation and capital adequacy requirements. Difficulty: Extreme.

- Set up a SIPP (Self Invested Personal Pension) firm and have investors invest in Company X via Company Y SIPPs, while failing to do adequate due diligence. (Note: rulings from the Ombudsman have been contradictory, but the recent direction of travel seems to be that the SIPP provider can be held liable.) Problem: getting authorisation to run a SIPP provider also involves stringent regulation and capital adequacy. Difficulty: Extreme.

- Set up a financial adviser and have it advise investors to invest in Company X. Problem: Getting authorisation to give advice requires passing a series of exams and obtaining professional indemnity insurance. Difficulty: Much lower than setting up a bank or a SIPP provider, but still high enough to prove a deterrent.

The crucial difference between these three types of firm and Independent Portfolio Managers is that they all involve a specific type of FCA permission that is quite hard to get.

However, any FCA authorised firm, regardless of what it is authorised to do, is permitted by the Financial Services And Markets Act to authorise financial promotions. There is no specific FCA permission for “authorising financial promotions”. If you’ve got any other FCA authorisation, you get that one chucked in as a freebie.

In turn, following the recent precedent, any FCA-authorised firm can be ordered by the Ombudsman to pay for authorising promotions that they shouldn’t have.

Lowering the bar

There are FCA permissions that are really not that difficult to acquire – for example, insurance mediation (which has been a favourite of firms illegally holding themselves out as financial advisers when they don’t have the specific authorisation) or debt counselling.

You still have to wait six months to a year for the FCA to consider your application, but if you are in the unregulated investment bond business, a waiting period of six months to a year is not much of a problem.

According to the FCA’s website, “positive indicators” which would make authorisation more likely include:

- reading information on our website

- making enquiries of the contact centre

- seeking legal/compliance advice

- being able to clearly articulate their regulatory obligations

This sounds not dissimilar to the basic requirements for passing a job interview.

You get the point. Getting FCA authorisation is not difficult as long as you pick the right kind of authorisation. The authorisation of firms like Independent Portfolio Managers rather proves as much.

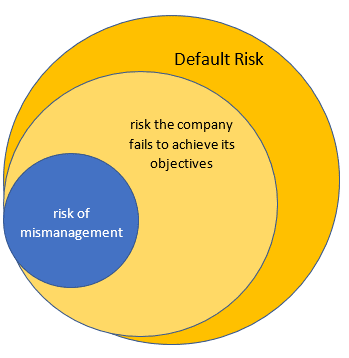

This means that allowing any FCA-authorised firm to effectively transfer the liability of an unregulated investment to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, by way of authorising a misleading or flawed promotion on its behalf which investors could then complain about, would represent an astonishing lowering of the bar to obtain FSCS coverage.

It is such a low bar that I can’t see why you wouldn’t do it, and make your investment far more attractive by lowering the risk at no cost to yourself. Hence my rather clickbaity headline.

Protected claims

But is it even likely? By my reading of the Financial Services Compensation Scheme rules, the answer is no.

As I have banged on about before, the liability of the Financial Services Compensation Scheme is strictly defined by the definition of a “protected claim”. All FSCS claims involve FCA-authorised firms but not all claims against FCA-authorised firms are covered by the FSCS. If I run an FCA-authorised company and commission my friend’s company to build me a £1 million solid gold swimming pool on the roof, and go bust without paying, my friend’s company has a claim against an FCA-authorised firm but not against the FSCS.

A complaint about a regulated adviser’s bad advice is a protected claim. So is a deposit-taker or a SIPP provider going bust. A claim arising from a complaint over the authorisation of investment literature is, as far as I can see, not included anywhere in the list of protected claims.

At this point of course, this is just my interpretation. It will be the Financial Services Compensation Scheme that decides when/if Independent Portfolio Managers eventually goes to the wall.

The regulated financial industry has long chafed against the cost of FSCS levies, on the grounds that the good guys have to pay for the bad. Making it much easier to get unregulated investments covered by the FSCS would inevitably lead to higher FSCS levies, and increase costs for the vast majority of consumers who use mainstream regulated financial services (who always pay in the end when investors in unregulated investments are bailed out).

If the FSCS does pay out over Secured Energy Bonds and Providence Bonds – even where no SIPPs were involved and no financial advice was involved – we can expect a huge backlash from the regulated world.

More likely is that the FSCS will reject the claims, and the Secured Energy and Providence investors will finally be allowed to come to terms with the loss of their investments.